Thick, white layers of fog pressed against the windows of my rental car as I ascended the narrow lanes of Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park. Deemed a National Historic Landmark, National Historic Place, and a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, the windy road traverses 50 miles between the east and west park entrances, crossing the Continental Divide at an altitude of over 6,000 feet along the way.

Built between 1921 and 1933, the majority of this two-lane road is bordered by a disturbingly short wall of rocks that separates a non-existent shoulder from a sheer drop off into the valley below. As I slowed to take each hairpin curve on the way up to Logan Pass that morning, I could hear my friend Olivia grinding her teeth and digging her fingernails into the passenger seat cushion. After the fourth or fifth time, she grumbled something I could barely understand from between her clenched teeth.

“What’s that?” I asked her.

“You need to STAY ON THE YELLOW LINE. You are getting TOO CLOSE TO THE EDGE.”

“But I don’t want to get too close to cars coming down the other way, I might hit someone.”

“Better to hit ANOTHER CAR then to GO OFF THE CLIFF. That’s how you are SUPPOSED TO DRIVE in the MOUNTAINS.”

It was then that I realized we’d made a critical mistake. Olivia, a native of Idaho who grew up driving on twisty two-lane roads, was not on the car rental paperwork and therefore not the chosen driver for this mountain road trip. Instead, our lives were in my hands — me, the Floridian flatlander who didn’t know a damn thing about driving in these conditions.

Realizing I was lacking in some very crucial knowledge, Olivia slowly released her death grip on the seat and began to calmly coach me as we navigated our way across the park toward Saint Mary Lake.

We were, at that point, about five days into a week-long road trip that originated in Olivia’s hometown of Council, Idaho (read more about the whole road trip here, in Part 1: Idaho and Part 2: Montana).

“How glorious a greeting the sun gives the mountains.” – John Muir

If I could offer you one and only one piece of advice about visiting Glacier National Park, it would be this: Do not go during the first week of August.

Quite the opposite of my offseason trip to Yosemite, this peak season visit to Glacier underscored some of the major problems our National Parks are currently facing with overcrowding.

With so many visitors packing the parks, we had to scoop up our campsite at Flathead Lake State Park before dawn and hustle up the road just to secure a first come, first served spot at one of Glacier’s packed campgrounds. At just after 7:30 a.m., we managed to snag the very last open site at Apgar Campground near the park’s west entrance. We quickly threw our tent back up and headed out to explore.

Glacier National Park encompasses more than a million acres of preserved land along the US-Canada border in Montana. Home to grizzly bears, moose, mountain goats, and some endangered animals like wolverines and Canadian lynxes, the park includes parts of two separate mountain ranges. These mountain ranges were originally inhabited by the Flathead and Blackfeet Indian Tribes, both of which now have reservations that border the park.

On busy summer days, every parking lot and scenic pull-off along Going-to-the-Sun Road fills up by mid-morning. In an effort to reduce parking troubles, facilitate visitors’ explorations, and cut down on emissions, Glacier offers shuttles that can carry passengers back and forth across the park. Unfortunately, the tight curves along the way to Logan’s Pass only allow vehicles up to a certain size to make the journey. So, instead of being able to ferry 40 or 50 people at a time in a big bus, each of Glacier’s smaller shuttles only carry about 20 folks apiece.

Subsequently, we waited in line for two hours (TWO HOURS) at the Apgar Visitor Center to catch a shuttle up the road. For a moment I thought I was at a theme park instead of a National Park. Still, once we finally got on board, the shuttle was worth the wait because the big picture windows allowed us to take in the stunning views as we ascended to the Continental Divide.

Prior to our arrival, Olivia and I had carefully studied hiking maps for Glacier and selected what appeared to be a relatively easy trail hike from the Logan’s Pass Visitor Center up to Hidden Lake. One of the park rangers at the Visitor Center assured us the trail wasn’t much more than a short “very flat” walk. We stepped out of the crowded gift shop and followed the signs around back to the trailhead. It became very apparent to us very quickly that the park ranger either blatantly lied to us or did not have a fundamental understanding of the word “flat.”

|

|

|

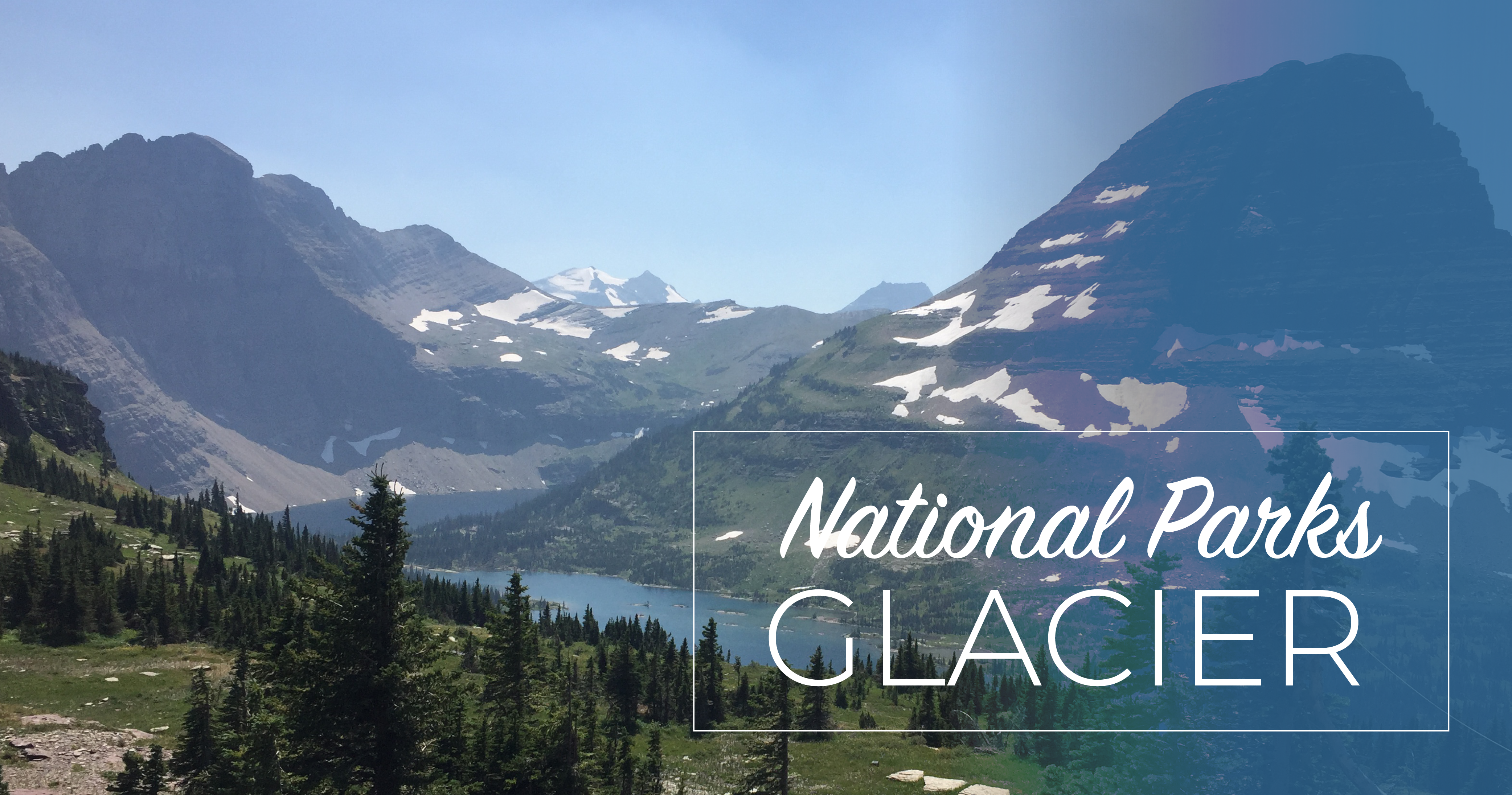

With an elevation gain of 540 feet, the popular trail is made up of a series of raised boardwalks and stairs (yes, stairs, which are by nature NOT flat) that take visitors to a maximum altitude of 7,152 feet. On the day of our visit, temperatures were close to 80 degrees, but a few patches of snow still lingered in the shadows of the surrounding mountains. As we climbed the alpine meadow slope, we took periodic breaks not only to chug some water and apply more sunscreen, but also just to stop and absorb the panoramic vistas around us.

Because the trail climbs above the natural treeline, there’s nothing to obscure your view of the park’s tallest peaks. Near the apex of the trail, we caught our first view of Hidden Lake. It’s about another mile from that point down to the lake itself, but knowing we were going to have another long wait to catch a shuttle back to the campground, we decided to head back.

|

|

“The wheels and springs of man are all set to the hypothesis of the permanence of nature.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Enfolded inside a dense pine forest, the Apgar Campground was the perfect respite at the end of a long day. We originally planned to attend a park ranger presentation at the campground’s amphitheater, but once we got back to our campsite we decided to stay put for the night. Olivia tied up her hammock between a couple of trees and I settled into one of the camp chairs we brought along with a craft beer and a good book. The day’s heat dissolved, leaving a soft, chilly breeze to rustle the branches overhead.

|

|

Now, I’m not going to lie to you. I don’t have a lot of tent camping experience and those two nights sleeping on the ground were not my favorite. The ground, in case you are not aware, is quite hard. I wanted to bring an air mattress, but Olivia is a tent camping traditionalist and so it was sleeping bags on the hard Earth for us. It also didn’t help my sleeping habits that every single sound I heard during the night sounded like a bear clomping through the woods on his way to eat me.

On our second morning in the park, we packed up our gear and started that harrowing, foggy trip up Going-to-the-Sun Road. Since we didn’t make it past Logan’s Pass the first day, we wanted to see the east side of Glacier including Saint Mary Lake, Two Medicine and the Many Glacier Lodge.

“Nature and books belong to the eyes that see them.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Although it’s a bit out of the way to exit the park at Saint Mary and travel another hour or so north to reach Many Glacier and an hour south to reach Two Medicine, it was well worth it. Much less crowded than the west side of the park, these two more remote spots were picturesque even on a gray, overcast day.

We started at the Many Glacier Lodge, a small chalet-style hotel built in 1915 on Swiftcurrent Lake. This hotel, as well as the Glacier Park Lodge, were both erected by the Great Northern Railway, which crosses the Continental Divide along the southern border of the park. The railway was completed in 1890, and they promoted the area as a premiere destination in order to drive business with visitors from both sides of the US.

While of course it’s the natural resources of these National Parks that I love the most, I also have a strong affinity for these old feats of architecture and construction. Old Faithful Lodge is my favorite, Grand Canyon Lodge is another, and Many Glacier ranks up there as well. The craftsmanship and woodwork in these places — which you know was all done by hand — is really remarkable.

Aside from the views of the lake and mountains beyond, my favorite feature inside the lodge was a massive stone fireplace with a three-story, copper flue that ran up the center of the hotel atrium. We grabbed elk sausage croissants from the lodge’s cafe and ate them on a bench beside the lake (a five-star breakfast experience if I’ve ever had one).

|

|

|

Heading south down to Missoula, where we planned to stay with some friends for the night, we stopped off at our last destination within Glacier National Park: Two Medicine. This part of the park, everything east of the Continental Divide, once belonged to the Blackfeet Tribe. The mountains in this area, especially Chief Mountain and Two Medicine, were considered the “Backbone of the World” to the Blackfeet, who frequented the region on vision quests. In 1895, the tribe sold this part of the land to the US Government for $1.5 million.

Today, Two Medicine is a quiet little area with a campground, general store and a few peaceful trails along Two Medicine Lake. It was still chilly out on the day of our visit — a thirty degree temperature change from the day before — so we were glad to find some hot cocoa at the general store before taking a little walk along the lakeshore.

“Though we travel the world over to find the beautiful, we must carry it with us or we find it not.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

We left our final stop at Glacier and pointed our trusty rental car south toward Missoula. Leaving nature and returning to the city (albeit a quiet municipality like Missoula) always makes me a little sad. But with each of these beautiful places I visit, I try to tuck a piece of its natural spirit deep in my heart so that I can carry it with me as I go along my journey. Glacier will stay with me for a long time to come, never more than a quick memory away.